You’re a runner and the outside of your knee starts hurting after a few miles?

It might be IT band syndrome.

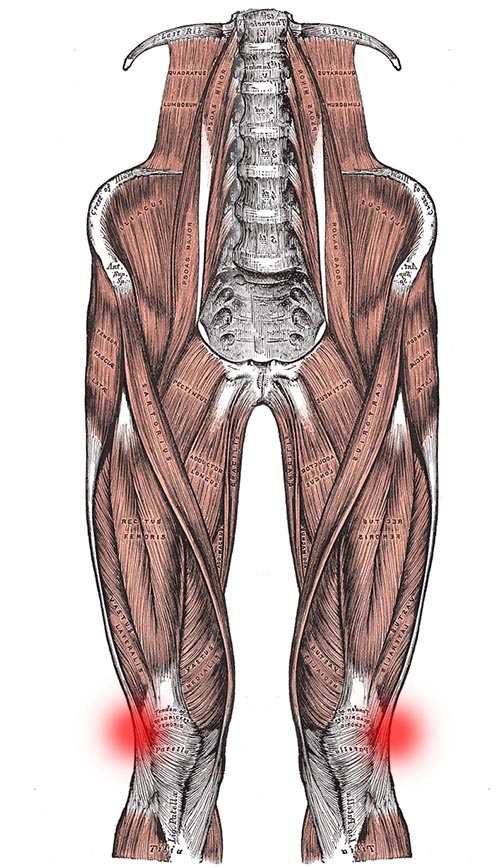

Iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS) is the most common type of pain on the side of the knee and the second most common running injury1 overall. It can also affect people in other sports that require repeated knee flexion, such as cycling, skiing, or weightlifting2.

Symptoms and Diagnosis

Your doctor will diagnose your injury based on your history, your symptoms, and a physical examination.

The symptoms of ITBS are having a burning or stabbing pain on the outside of the knee3 that may only set in after a certain mileage or time4. The outer side of the knee may also be tender to the touch5, especially when the knee is bent6. Knee flexion may be accompanied by popping sounds and a popping sensation on the side of the knee can occur7.

Two common physical examinations performed for iliotibial band syndrome are Ober’s test8 and Noble’s test9. Ober’s test helps physicians determine if the tensor fascia latae muscle is tight10, whereas in Noble’s test the physician palpates the injury site in the range of motion commonly painful for people with ITBS.

If necessary, MRI can be used to rule out intra-articular injuries such as lateral meniscus tears11. Other injuries with a similar pathology that your doctor will have to exclude through differential diagnosis include biceps femoris tendinopathy, degenerative joint diseases, LCL sprain, Patellofemoral stress syndrome, and popliteal tendinopathy12.

Summary of ITBS Symptoms:

- Pain on the outer side of the knee

- Sharp or burning pain

- Pain worse walking down hills or stairs

- Pain sets in after a certain time or mileage

Causes

Unfortunately the quality of the research on IT band syndrome is still poor and results are often conflicting13. There is no consensus on the exact cause of the pain14.

One theory is that ITBS is caused by friction between the IT band and a part of the thighbone (lateral femoral epicondyle, LFE)15 which then leads to inflammation of that part of the band16.

A newer theory is that ITBS is instead caused by excessive compression of the IT band against the LFE17, which then compresses an unknown tissue beneath the band18. According to this hypothesis, it’s not the iliotibial band itself that is painful, but a “fibrous attachment to the femur [thighbone] and the surrounding fat.”19

The newer theory is supported by MRI findings that showed signal changes under the IT band20 as well as cadaver studies21 and the fact that surgery on that mystery tissue via “resection of lateral synovial recess” has produced good results22.

Risk Factors

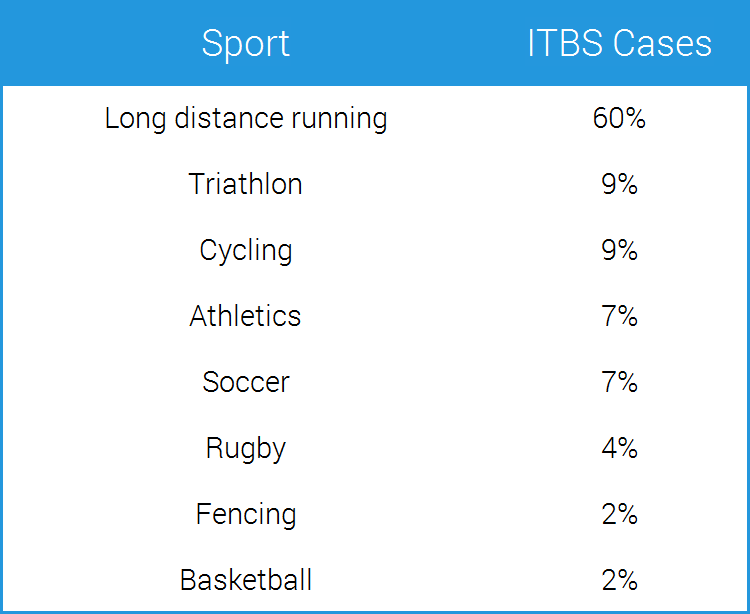

Long-distance runners are at a significantly greater risk of suffering ITBS than athletes from other sports23. Other risk factors are running on a composition track, especially if you only run in one direction, and running a higher weekly mileage24. Women may also be at higher risk25.

Compared to an uninjured control group, runners with iliotibial band syndrome trained more, but at the same time they were less experienced runners26.

Researchers also examined movement differences between runners with ITBS and healthy controls. These studies found reduced hip abductor strength27, greater hip adduction and knee internal rotation28, as well as more trunk flexion on the affected side29 in those with IT band syndrome.

However, these studies examined people that were already injured, which is why it’s unclear whether the mentioned factors were cause or effect of the ITBS. In other words, it’s possible that the IT band pain caused these changes and not the other way around.

Other research also found that a positive Ober’s test, which clinicians use to assess IT band tightness, was not predictive of ITBS risk30 and that weakness of the hip abductors did not seem to cause the injury31.

Treatment

Unfortunately no one treatment for iliotibial band syndrome has been shown to work best32 and the only thing researches agree on is that during rehab you need to avoid painful activities and movements33.

Here’s what we do know.

Resting is the most important step since continued tissue irritation will prolong the recovery process. In mild cases it may be enough to stay below the mileage at which pain sets in, but complete rest from running can also be necessary34.

Two common tendencies among avid athletes are to not rest seriously enough (so they keep training) and to not rest long enough. Instead, take this seriously and expect to go through at least two to six weeks of rest35.

Icing is another low-risk treatment option to achieve pain relief. You can ice as often as every 10 minutes36. Check out my video on icing to learn more about how to do it, just be sure to ice the painful spot on the side of your knee instead of the area shown in the video.

IT Band Massage

Another common ITBS treatment is massaging the IT band, although it is somewhat controversial. The goals of the massage are to release trigger points, to remove adhesions, and to lengthen the tissue.

However, the IT band cannot have trigger points, since it’s not a muscle37 and stretches have a barely measurably effect, because the IT band is firmly attached to the thighbone along the bone’s full length38.

The IT band also cannot have adhesions, since it’s not a muscle or several tissues gliding on top of each other.

For these reasons massaging the IT band has been criticized as a waste of time over recent years, yet some people still swear by it. In spite of the controversy I’d at least try it to see if it has a positive effect. If not, no harm done.

Another approach to reduce IT band tension is to massage and stretch (if necessary) muscles that connect to it such as the gluteus maximus39, the tensor fascia latae40, and the peroneus longus41.

I also recommend you extend your massage to the quadriceps muscles, the calves, and the gluteus medius, since they can also contribute to knee pain.

In addition to the massage you can mobilize the hip muscles that attach to the IT band with the following two mobility exercises.

Seated 90/90 Mobilization

Lying Knee Pull-In

Strengthening Exercises

Strengthening exercises for IT band syndrome have also produced good results in some studies42. These exercises include gluteus medius strengthening through hip abductions and step downs with the supporting leg kept straight.

The one caveat about massage, stretching, mobility, and strengthening work is that there’s no consensus on what role muscle strength deficits and imbalances play for ITBS43 and that a small number of people will still not get better even after doing all these exercises religiously44. The good news is that there are still other options.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatories are also used to treat IT band syndrome, but they showed only minimal benefits over placebo45. Additionally, oral NSAIDs can have serious side-effects such as headaches, nausea, or sore throat46, which is why using topical NSAIDs, such as Voltaren gel for example, are safer alternatives47 if you do want to try the anti-inflammatory option.

Surgery

In very stubborn cases of ITBS arthroscopic surgery may be necessary48, but this is not something to be feared as outcomes have been very favorable.

For example, in one study a “standardized resection of the lateral synovial recess” via arthroscopic surgery has produced good results in 32 of 33 patients (97%)49. In a follow-up study, the same technique achieved good or excellent results in 38 of 42 knees (90%)50.

All patients were able to return to sports after three months51.

Another surgical approach is open IT band bursectomy. However, two drawbacks compared to the arthroscopic approach mentioned above is that the results of the open bursectomy were not quite as good52 and that also it doesn’t allow the surgeon to correct intra-articular pathologies during the same procedure53.

Long-Term Prevention

Based on the available evidence, the following steps can help you with long-term prevention of IT band syndrome.

1) Increase running mileage slowly

Looking back at the evidence we can see that athletes with ITBS trained more, even though they were less experienced runners than the non-injured control group54, which makes sense because the more experienced you are, the better you know how much your body can handle.

ITBS is an overuse injury so the easiest step you can take to prevent it is to increase your weekly running mileage slowly, especially if you’re a novice runner. In this scenario, more isn’t better.

2) Improve where & how you run

Other changes can make to potentially reduce your risk of ITBS are to run on soft surfaces with less knee flexion. Running faster with a longer stride length may also help. Interestingly, this goes against the conventional running wisdom of running with short strides to reduce impact forces.

Avoid running slowly, running on hard roads, running on terrain that is slanted to one side, and running in the same direction on composition tracks.

If you want, experiment with switching to a mid- or forefoot strike, as this may also help lower risk of ITBS since it shifts some load away from the knee to the ankle.

3) If you’re a hiker…

If you’re a hiker with IT band syndrome, try using trekking poles, as they can reduce forces on the knee and ankle when walking down-hill55.

4) Keep up some maintenance work

If long-term health and performance are important to you, you should always keep up some maintenance work regardless of which sport you do. Just do a few exercises each day to neutralize imbalances your sport may cause or to strengthen supportive musculature that is important in your sport.

For example, weightlifters and overhead athletes need a healthy rotator cuff, whereas runners need their hip muscles to have normal function56.

The mobility and strengthening exercises listed above can help you with keeping your supporting musculature strong enough for running.

5) Cross-train with other sports

Athletes that participate in sports other than running are at a much lower risk of getting IT Band syndrome57, so if you want to prevent ITBS, cross-train with other sports.

You could pick yoga, badminton, wrestling, swimming, bouldering, or weightlifting, for example. Just make sure it’s something you enjoy.

Finally, the most important step you need to take is to avoid everything that irritates the area.

[1] J. E. Taunton, “A retrospective case-control analysis of 2002 running injuries,” British Journal of Sports Medicine 36, no. 2 (2002): 96.

[2] C. A. Lucas, “Iliotibial band friction syndrome as exhibited in athletes,” Journal of athletic training 27, no. 3 (1992): 250.

[3] S. Grau et al., “Kinematic classification of iliotibial band syndrome in runners,” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 21, no. 2 (2011): 185.

[4] Ibid., p. 185.

[5] STEPHEN P. MESSIER et al., “Etiology of iliotibial band friction syndrome in distance runners,” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 27, no. 7 (1995): 951.

[6] STEPHEN P. MESSIER et al., “Etiology of iliotibial band friction syndrome in distance runners,” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 27, no. 7 (1995): 952; S. Grau et al., “Kinematic classification of iliotibial band syndrome in runners,” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 21, no. 2 (2011): 185.

[7] Corey Beals and David Flanigan, “A Review of Treatments for Iliotibial Band Syndrome in the Athletic Population,” Journal of Sports Medicine 2013, no. 3 (2013): 2.

[8] Michael Fredericson and Adam Weir, “Practical Management of Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome in Runners,” Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 16, no. 3 (2006): 263; Corey Beals and David Flanigan, “A Review of Treatments for Iliotibial Band Syndrome in the Athletic Population,” Journal of Sports Medicine 2013, no. 3 (2013): 2.

[9] Michael Fredericson and Adam Weir, “Practical Management of Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome in Runners,” Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 16, no. 3 (2006): 263; S. Grau et al., “Kinematic classification of iliotibial band syndrome in runners,” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 21, no. 2 (2011): 185.

[10] Gilbert M. Willett et al., “An Anatomic Investigation of the Ober Test,” The American Journal of Sports Medicine 44, no. 3 (2016).

[11] Corey Beals and David Flanigan, “A Review of Treatments for Iliotibial Band Syndrome in the Athletic Population,” Journal of Sports Medicine 2013, no. 3 (2013): 2.

[12] Razib Khaund and Sharon Flynn, “Iliotibial Band Syndrome: A Common Source of Knee Pain,” American Academy of Family Physicians 71, no. 8 (2005): 1547, https://www.aafp.org/afp/2005/0415/p1545.html, accessed December 2019.

[13] van der Worp, Maarten P. et al., “Iliotibial Band Syndrome in Runners,” Sports Medicine 42, no. 11 (2012).

[14] Corey Beals and David Flanigan, “A Review of Treatments for Iliotibial Band Syndrome in the Athletic Population,” Journal of Sports Medicine 2013, no. 3 (2013): 4.

[15] Razib Khaund and Sharon Flynn, “Iliotibial Band Syndrome: A Common Source of Knee Pain,” American Academy of Family Physicians 71, no. 8 (2005): 1545, https://www.aafp.org/afp/2005/0415/p1545.html, accessed December 2019; Michael Fredericson and Adam Weir, “Practical Management of Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome in Runners,” Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 16, no. 3 (2006): 261.

[16] Corey Beals and David Flanigan, “A Review of Treatments for Iliotibial Band Syndrome in the Athletic Population,” Journal of Sports Medicine 2013, no. 3 (2013): 1.

[17] Jodi Aderem and Quinette A. Louw, “Biomechanical risk factors associated with iliotibial band syndrome in runners: a systematic review,” BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 16, no. 1 (2015): 95, accessed December 2019.

[18] S. Grau et al., “Kinematic classification of iliotibial band syndrome in runners,” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 21, no. 2 (2011): 184.

[19] F. Michels et al., “An arthroscopic technique to treat the iliotibial band syndrome,” Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 17, no. 3 (2009).

[20] Michael Fredericson and Adam Weir, “Practical Management of Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome in Runners,” Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 16, no. 3 (2006): 265; STEPHEN P. MESSIER et al., “Etiology of iliotibial band friction syndrome in distance runners,” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 27, no. 7 (1995): 952; G. Nishimura et al., “MR findings in iliotibial band syndrome,” Skeletal Radiology 26, no. 9 (1997); Claus Muhle et al., “Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome: MR Imaging Findings in 16 Patients and MR Arthrographic Study of Six Cadaveric Knees,” Radiology 212, no. 1 (1999).

[21] Michael Fredericson and Adam Weir, “Practical Management of Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome in Runners,” Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 16, no. 3 (2006): 261.

[22] F. Michels et al., “An arthroscopic technique to treat the iliotibial band syndrome,” Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 17, no. 3 (2009); Sanaz Hariri et al., “Treatment of Recalcitrant Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome with Open Iliotibial Band Bursectomy,” The American Journal of Sports Medicine 37, no. 7 (2009); Frederick Michels and Stephane Jambou, “The iliotibial band syndrome treated with an arthroscopic technique in 40 patients,” ScienceMED 2, no. 2 (2011): 179, http://www.edlearning.it/ScienceMED/v2_2_2011.pdf, accessed December 2019.

[23] Frederick Michels and Stephane Jambou, “The iliotibial band syndrome treated with an arthroscopic technique in 40 patients,” ScienceMED 2, no. 2 (2011): 180, http://www.edlearning.it/ScienceMED/v2_2_2011.pdf, accessed December 2019.

[24] STEPHEN P. MESSIER et al., “Etiology of iliotibial band friction syndrome in distance runners,” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 27, no. 7 (1995): 955.

[25] S. Grau et al., “Kinematic classification of iliotibial band syndrome in runners,” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 21, no. 2 (2011): 187.

[26] STEPHEN P. MESSIER et al., “Etiology of iliotibial band friction syndrome in distance runners,” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 27, no. 7 (1995): 957.

[27] Jodi Aderem and Quinette A. Louw, “Biomechanical risk factors associated with iliotibial band syndrome in runners: a systematic review,” BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 16, no. 1 (2015): 96, accessed December 2019; S. Grau et al., “Kinematic classification of iliotibial band syndrome in runners,” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 21, no. 2 (2011): 187.

[28] Brian Noehren, Irene Davis, and Joseph Hamill, “ASB Clinical Biomechanics Award Winner 2006,” Clinical Biomechanics 22, no. 9 (2007); Reed Ferber et al., “Competitive Female Runners With a History of Iliotibial Band Syndrome Demonstrate Atypical Hip and Knee Kinematics,” Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 40, no. 2 (2010).

[29] Eric Foch et al., “Associations between iliotibial band injury status and running biomechanics in women,” Gait & Posture 41, no. 2 (2015).

[30] Michelle R. Devan et al., “A Prospective Study of Overuse Knee Injuries Among Female Athletes With Muscle Imbalances and Structural Abnormalities,” Journal of athletic training 39, no. 3 (2004): 267.

[31] S. Grau et al., “Hip Abductor Weakness is not the Cause for Iliotibial Band Syndrome,” International Journal of Sports Medicine 29, no. 7 (2008).

[32] Corey Beals and David Flanigan, “A Review of Treatments for Iliotibial Band Syndrome in the Athletic Population,” Journal of Sports Medicine 2013, no. 3 (2013): 2.

[33] Michael Fredericson et al., “Hip Abductor Weakness in Distance Runners with Iliotibial Band Syndrome,” Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 10, no. 3 (2000): 172.

[34] Michael Fredericson and Adam Weir, “Practical Management of Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome in Runners,” Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 16, no. 3 (2006): 265.

[35] Corey Beals and David Flanigan, “A Review of Treatments for Iliotibial Band Syndrome in the Athletic Population,” Journal of Sports Medicine 2013, no. 3 (2013): 4.

[36] Michael Fredericson and Adam Weir, “Practical Management of Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome in Runners,” Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 16, no. 3 (2006): 265.

[37] Ibid., p. 261.

[38] E. C. Falvey et al., “Iliotibial band syndrome: an examination of the evidence behind a number of treatment options,” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 20, no. 4 (2010).

[39] Michael Fredericson and Adam Weir, “Practical Management of Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome in Runners,” Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 16, no. 3 (2006): 261.

[40] STEPHEN P. MESSIER et al., “Etiology of iliotibial band friction syndrome in distance runners,” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 27, no. 7 (1995): 951.

[41] Jan Wilke et al., “Anatomical study of the morphological continuity between iliotibial tract and the fibularis longus fascia,” Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy 38, no. 3 (2016).

[42] Michael Fredericson et al., “Hip Abductor Weakness in Distance Runners with Iliotibial Band Syndrome,” Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 10, no. 3 (2000): 173.

[43] Maryke Louw and Clare Deary, “The biomechanical variables involved in the aetiology of iliotibial band syndrome in distance runners – A systematic review of the literature,” Physical Therapy in Sport 15, no. 1 (2014); S. Grau et al., “Hip Abductor Weakness is not the Cause for Iliotibial Band Syndrome,” International Journal of Sports Medicine 29, no. 7 (2008).

[44] R. Pinshaw, V. Atlas, and T. D. Noakes, “The nature and response to therapy of 196 consecutive injuries seen at a runners' clinic,” South African medical journal = Suid-Afrikaanse tydskrif vir geneeskunde 65, no. 8 (1984).

[45] M. P. Schwellnus et al., “Anti-inflammatory and combined anti-inflammatory/analgesic medication in the early management of iliotibial band friction syndrome. A clinical trial,” South African medical journal = Suid-Afrikaanse tydskrif vir geneeskunde 79, no. 10 (1991): 604.

[46] Ibid., p. 605.

[47] Patricia McGettigan, David Henry, and Fiona M. Turnbull, “Use of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs That Elevate Cardiovascular Risk: An Examination of Sales and Essential Medicines Lists in Low-, Middle-, and High-Income Countries,” PLoS Medicine 10, no. 2 (2013).

[48] C. A. Lucas, “Iliotibial band friction syndrome as exhibited in athletes,” Journal of athletic training 27, no. 3 (1992): 252.

[49] F. Michels et al., “An arthroscopic technique to treat the iliotibial band syndrome,” Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 17, no. 3 (2009).

[50] Frederick Michels and Stephane Jambou, “The iliotibial band syndrome treated with an arthroscopic technique in 40 patients,” ScienceMED 2, no. 2 (2011): 179, http://www.edlearning.it/ScienceMED/v2_2_2011.pdf, accessed December 2019.

[51] Ibid., p. 181.

[52] Sanaz Hariri et al., “Treatment of Recalcitrant Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome with Open Iliotibial Band Bursectomy,” The American Journal of Sports Medicine 37, no. 7 (2009).

[53] F. Michels et al., “An arthroscopic technique to treat the iliotibial band syndrome,” Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 17, no. 3 (2009).

[54] STEPHEN P. MESSIER et al., “Etiology of iliotibial band friction syndrome in distance runners,” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 27, no. 7 (1995): 957.

[55] MICHAEL BOHNE and JULIANNE ABENDROTH-SMITH, “Effects of Hiking Downhill Using Trekking Poles while Carrying External Loads,” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 39, no. 1 (2007).

[56] Roger A. Mann, Gary T. Moran, and Sandra E. Dougherty, “Comparative electromyography of the lower extremity in jogging, running, and sprinting,” The American Journal of Sports Medicine 14, no. 6 (2016).

[57] Frederick Michels and Stephane Jambou, “The iliotibial band syndrome treated with an arthroscopic technique in 40 patients,” ScienceMED 2, no. 2 (2011): 180, http://www.edlearning.it/ScienceMED/v2_2_2011.pdf, accessed December 2019.