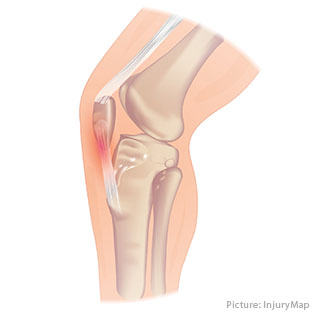

Patellar tendonitis is an injury of the tendon that connects your kneecap – the patella – to your shinbone.

Patellar tendonitis is an injury of the tendon that connects your kneecap – the patella – to your shinbone.

You use the patellar tendon every time you extend your leg, like when you’re kicking, running, or jumping, which is why patellar tendonitis is most common in jumping sports such as volleyball or basketball. However, it can occur in non-athletes as well.

Getting rid of patellar tendonitis can take anywhere between less than 3 months1 and up to 15 years2. The key to a fast recovery is doing the right things early on and avoiding certain treatment mistakes that cause setbacks. This page will tell you everything you need to know.

2-Minute Summary (TLDR):

Patellar tendonitis is a frustrating injury because it rarely heals on its own — even with rest. Without the right approach, it can drag on for months or years. The most common symptom is pain where the patellar tendon attaches to the kneecap. This spot can hurt during squats, jumps, or even when pressed.

Many treatments promise quick results, but decades of research show that the most reliable method is progressive loading with slow strengthening exercises such as isometrics or isotonics (think wall sit or slow squat). When you scale these exercises carefully, remove hidden blockers to healing, and correct biomechanical overload, recovery can happen in as little as four weeks — as some of my course participants have shown.

Mistakes, however, can easily turn a short recovery into many months or even years.

If you want to follow the same research-based process I use with my clients, I’ve created a free step-by-step course called Tendonitis Insights. Thousands have already used it successfully — you can sign up here, or keep reading the detailed research briefing below.

“First, thank you so much for your course on healing patellar tendinitis! I’ve been dealing with it for nearly 11 months, and did physical therapy for 3 months with less progress than I’ve had in 2 weeks following your advice. It’s amazing.”

— Jacob L.

Symptoms

In patellar tendonitis the pain will only be on the front of the knee. You will feel it directly in the patellar tendon, either right below the kneecap or where the patellar tendon attaches to the shinbone.

The pain will get worse with activities such as running, jumping, squatting, kneeling, or sitting, and although the pain response is usually immediate, it can also take up to 48 hours to set in.

In the early stages of patellar tendonitis you will only get pain after intense exercise or sports, but as the injury progresses you may begin to feel it during sports and later on even while at rest. The sooner you start rehab, the shorter your recovery will be.

You need to see a doctor immediately if you have one of the following symptoms:

- Your knee is swollen or red

- Your pain is getting worse or is very sharp

- Your pain prevents you from doing everyday activities

- You have a locking sensation in your knee

- Your knee feels unstable

You’re still not sure? Read our report about symptoms and diagnosis of patellar tendonitis.

Causes

The most common cause of patellar tendonitis is repeated overuse of the tendon over a longer period of time. Usually this overuse is a combination of training too hard and training too frequently.

Repeated overuse interrupts the tendon’s attempts to grow stronger in response to the training loads and as this continues, cellular changes inside the tendon begin to occur3. Unless the overuse is stopped, the tendon will slowly begin to grow weaker, which in turn makes future overuse more likely.

That’s why training through the pain can add months to your recovery time.

Contrary to popular belief tendonitis is NOT caused by inflammation.4 Inflammation does play a minor role in the injury5, but tendonitis is not an inflammatory response per se, which is why suppressing inflammation through anti-inflammatories will actually be detrimental in most situations (see section on treatment below).

A less frequent cause of patellar tendonitis is direct trauma to the tendon6, like suffering a fall or getting hit in the knee.

If you want to learn more, you can read our article on Hidden Causes and Risk Factors of Patellar Tendonitis: Why Jumper’s Knee Keeps Coming Back.

Risk Factors

Risk factors for patellar tendonitis include:

- High training volume7 (e.g., 8.94-times normal risk for more than 20 hours of weekly training time8)

- Big increases in training load and or training volume9

- Having a higher vertical leap10

- Muscular problems such as tight hamstrings, calves, or quadriceps muscles11

- Improper jumping mechanics12

- Training on hard surfaces13

- Participation in jumping sports14, especially volleyball15 or basketball16

- No gradual return to sports after a rest period of 6+ weeks17

- Diabetes18

- Older age (odds ratio of 4.209)19

- Abnormal estrogen levels20

- Central adiposity for men and peripheral adiposity for women21

- Autoimmune or connective tissue diseases (e.g., psoriatic arthritis)22

5 Tendonitis Mistakes That Add Years to Your Recovery Time

See you in the course.

Diagnosis

Your doctor will diagnose your injury by inquiring about your history and by using a combination of manual examinations23 and imaging tests such as ultrasound or MRI.

MRIs and x-rays are also used for differential diagnosis, to rule out other knee injuries with similar symptoms. Learn more about the symptoms of patellar tendonitis.

However, in some cases patellar tendonitis is difficult to diagnose, because tendons can be painful with a normal ultrasound,24 just like tendons that show pathological changes on ultrasound can still be pain-free.25

Treatments

A variety of treatments for patellar tendonitis are available, but not all are equally effective. I’ve reviewed and analyzed the available research — including thousands of studies — and distilled the most reliable, evidence-based approaches into a simple at-home program. You can explore the core principles of this program in my free Tendonitis Insights course at the bottom of this page.

Here is an overview of what research has discovered:

Medication

Your doctor may prescribe pain relievers or non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs). NSAIDs can provide short-term pain relief26 and they are a viable option during the early stages of patellar tendonitis, but they actually slow down tendon repair once the injury has become chronic.27

Physical Therapy

Physical therapy with slow strengthening exercises such as eccentric squats,28 leg presses,29 or leg extensions30 have been shown to be very effective for providing long-term improvement. Here’s an in-depth look at the best exercises for patellar tendonitis.

Isometric holds, i.e. holding the weight in place instead of moving it, have also delivered promising results by reducing pain and muscular inhibition.31

Additionally, stretching exercises, like quad or hamstring stretches, can help prevent patellar tendonitis 32 and combined with strengthening drills they can produce superior treatment outcomes, compared to just doing strengthening alone33. However, in some cases stretching leads to a flare-up of pain, which is why caution is always advised.

With the right approach, treatment at home can work just as well as physical therapy. The keys are using the right progression and avoiding common pitfalls that can cause setbacks.

Talk to your doctor before starting any exercise regimen.

Rehabilitation Timeline

If you take the right steps at the right time, here’s the average recovery timeline you can expect. If your recovery is taking longer, it often means there are hidden factors overloading the tendon or slowing its repair. The Koban Method for patellar tendonitis is designed to address these issues with a clear, step-by-step approach. You can explore the key principles in my free Tendonitis Insights course — there’s a sign-up link at the bottom of this page.

| Phase | Duration | Goals |

|---|---|---|

| Early Stage | 0–4 weeks | Pain reduction, isometric holds, maintain general fitness |

| Mid Stage | 4–8 weeks | Introduce eccentric loading, gradually increase volume |

| Late Stage | 8–16 weeks | Sport-specific drills, plyometrics, full return to activity |

Again: these time frames are averages. Your exact progression will depend on pain levels, tendon adaptation, history, and how well your training avoids the many pitfalls that can cause setbacks or delays.

Common Mistakes That Delay Recovery

- Training with too much pain – can cause tendon degeneration.

- Relying solely on rest – causes tendon weakness and longer rehab.

- Overusing anti-inflammatories – may impair tendon healing and cause worse overall outcome.

- Skipping progressive overload – without gradual load increases to regain strength the tendon stays weak.

Adjunct Treatments

The physical therapy exercises can be combined with adjunct treatments, but unfortunately there is no strong evidence that proves these treatments provide long-term benefits.34

Icing is a good option for pain management and to manage flare-ups, but it didn’t show any benefits in treating tendonitis35 and it will temporarily decrease tendon flexibility.36

Wearing a patellar tendon strap can lead to a short-term pain reduction in patients with patellar tendonitis.37 It can also improve body awareness,38 jumping mechanics,39 and it may contribute to improved patellar tracking40. However, patellar tendon straps do not increase jumping performance41 and will not lead to long-term improvements.

Ultrasound therapy delivered inconsistent results as treatment for tendonitis42 and has failed to provide benefits in several studies.43

Iontophoresis can help drive a substance into body tissue by using an ionizing current44 and most commonly NSAIDs or corticosteroids are used for tendonitis. However, these treatments showed no improvement when compared to control groups.45

Invasive Procedures

Corticosteroid injections are inexpensive, easy to perform, and they carry a low risk of immediate complications.46 They can lead to a short-term reduction of pain, but they also increase risk of suffering a relapse.47 In one study on elbow tendonitis, 72% of patients treated with corticosteroid injections suffered a relapse.48

Unfortunately, over the long-term these injections will actually cause weaker tendons49 that are more prone to tearing.50

Platelet-rich plasma injections (PRP) are another popular treatment modality for patellar tendonitis. In this treatment centrifuged blood is injected into the injury site to speed up healing. Unfortunately there is little evidence to show an effect greater than placebo injections.51 However, PRP injections may be beneficial for recalcitrant cases of patellar tendonitis.

Prolotherapy and dry-needling are two other minimally invasive procedures for patellar tendonitis. Neither is supported by strong evidence.52

Surgery is a last resort treatment for refractory cases of patellar tendonitis,53 when all non-surgical options have been exhausted and the patient fully understands the risks and benefits of the respective procedure.54 It requires a longer rehab time of 6 to 12 months,55 but the long-term results are promising.56 For example, in one study surgery improved symptoms in 57% of patients.57

However, for non-recalcitrant cases of patellar tendonitis an exercise-based approach is a far superior option58 and performed correctly, it can produce outstanding results.

Prevention

Preventing patellar tendonitis is far easier than treating it once it has become chronic. The goal is to reduce excessive tendon loading while keeping your muscles, joints, and connective tissue healthy.

Warm-Up Routines

Begin each training session with at least 10 minutes of dynamic warm-up, including movements like walking lunges, high knees, and gentle squat pulses. This increases blood flow to the tendon and prepares it for load.59

Strength & Conditioning

Integrate lower-body strengthening 2–3 times per week, focusing on quads, glutes, and calves. Balanced muscle strength helps distribute forces evenly across the knee.

Surface & Footwear

Avoid prolonged training on concrete or other unforgiving surfaces.60 Wear sport-specific shoes with appropriate cushioning and support.

Progressive Load Increases

Increase training volume by no more than 10% per week to give your tendon time to adapt.61

For more details on preventive strategies, see our Patellar Tendonitis Prevention Guide.

Nutrition & Lifestyle for Tendon Healing

While no diet can “cure” patellar tendonitis, optimal nutrition supports tendon repair.

- Vitamin C & Collagen – may support collagen synthesis when taken before exercise.65

- Protein intake – aim for 1.0+ g/kg body weight to aid tissue repair.66

- Hydration – connective tissues function better when well-hydrated.

- Sleep – aim for 7–9 hours to promote tissue regeneration.67

Beyond these basics, certain dietary and lifestyle habits can silently weaken your tendons and even raise the risk of tears. For example, one common habit affects roughly 1.3 billion people worldwide and has been linked to a 53% reduction in tendon strength. I explain what it is — and how to avoid it — in the Tendonitis Insights course.

Myths vs Facts About Patellar Tendonitis

One aspect that makes recovery from patellar tendonitis so frustrating is the conflicting advice you will get. Here are some of the most common misconceptions.

| Myth | Fact |

|---|---|

| ❌ Patellar tendonitis is just inflammation | ✅ It’s primarily a degenerative process, not classic inflammation.4 |

| ❌ Rest alone will heal it | ✅ Without the right exercises, the pain will often come back. |

| ❌ Stretching will help you recover faster. | 🤔 Quad stretches can cause setbacks if used at the wrong time. |

| ❌ Strength training is all it takes to recover. | ✅ To prevent setbacks, you also need to fix biomechanics and hidden healing blockers. |

| ❌ Patellar straps cure tendonitis | ✅ They may reduce pain short-term but don’t heal the tendon. |

| ❌ Once it’s chronic, there’s nothing you can do. | ✅ I’ve helped people recover after years of pain. It’s all about using the right approach. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can patellar tendonitis heal on its own?

Mild cases may improve with rest and activity modification, but structured rehab is recommended to prevent recurrence.58

How long does recovery take?

Most recover in 3–6 months with proper rehab, but chronic cases may take a year or longer.55

Can I exercise with patellar tendonitis?

Yes, but you must avoid high-impact activities that aggravate symptoms. Focus on controlled strength training under guidance.28

What’s the difference between jumper’s knee and runner’s knee?

Jumper’s knee (patellar tendonitis) affects the patellar tendon, while runner’s knee (patellofemoral pain) involves the kneecap joint.16

5 Tendonitis Mistakes That Add Years to Your Recovery Time

See you in the course.

[1] J. L. Cook et al., “A cross sectional study of 100 athletes with jumper's knee managed conservatively and surgically. The Victorian Institute of Sport Tendon Study Group,” British journal of sports medicine 31, no. 4 (1997).

[2] M. Kongsgaard et al., “Corticosteroid injections, eccentric decline squat training and heavy slow resistance training in patellar tendinopathy,” Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports 19, no. 6 (2009).

[3] A. Del Buono et al., “Tendinopathy and inflammation: some truths,” International journal of immunopathology and pharmacology 24, 1 Suppl 2 (2011): 46.

[4] Ibid., p. 45.

[5] J. D. Rees, M. Stride, and A. Scott, “TENDONS: TIME TO REVISIT INFLAMMATION?,” British journal of sports medicine 47, no. 9 (2013).

[6] Giorgio Garau et al., “Traumatic patellar tendinopathy,” Disability & Rehabilitation 30, 20-22 (2008): 1616.

[7] Martin Hägglund, Johannes Zwerver, and Jan Ekstrand, “Epidemiology of patellar tendinopathy in elite male soccer players,” The American journal of sports medicine 39, no. 9 (2011).

[8] Sarah Morton et al., “Patellar Tendinopathy and Potential Risk Factors: An International Database of Cases and Controls,” Clinical journal of sport medicine : official journal of the Canadian Academy of Sport Medicine (2017).

[9] M. K. Drew and C. Purdam, “Time to bin the term ‘overuse’ injury: is ‘training load error’ a more accurate term?,” British journal of sports medicine 50, no. 22 (2016).

[10] Øystein Lian et al., “Performance characteristics of volleyball players with patellar tendinopathy,” The American journal of sports medicine 31, no. 3 (2003).

[11] Sarah Morton et al., “Patellar Tendinopathy and Potential Risk Factors: An International Database of Cases and Controls,” Clinical journal of sport medicine : official journal of the Canadian Academy of Sport Medicine (2017); E. Witvrouw et al., “Intrinsic risk factors for the development of patellar tendinitis in an athletic population. A two-year prospective study,” The American journal of sports medicine 29, no. 2 (2001); Peter Malliaras et al., “Patellar Tendinopathy: Clinical Diagnosis, Load Management, and Advice for Challenging Case Presentations,” The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy 45, no. 11 (2015): 895.

[12] van der Worp, H et al., “Jumper's knee or lander's knee? A systematic review of the relation between jump biomechanics and patellar tendinopathy,” International journal of sports medicine 35, no. 8 (2014).

[13] A. Ferretti, “Epidemiology of jumper's knee,” Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) 3, no. 4 (1986).

[14] Peter Malliaras, Lower Limb Tendinopathy Course (London, 31.10.2016).

[15] A. Ferretti, P. Papandrea, and F. Conteduca, “Knee injuries in volleyball,” Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) 10, no. 2 (1990).

[16] Ivo J. H. Tiemessen et al., “Risk factors for developing jumper's knee in sport and occupation: a review,” BMC research notes 2 (2009).

[17] Yu-Long Sun et al., “Temporal response of canine flexor tendon to limb suspension,” Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985) 109, no. 6 (2010); J. A. Hannafin et al., “Effect of stress deprivation and cyclic tensile loading on the material and morphologic properties of canine flexor digitorum profundus tendon: an in vitro study,” Journal of orthopaedic research : official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society 13, no. 6 (1995); James H.-C. Wang, Qianping Guo, and Bin Li, “Tendon Biomechanics and Mechanobiology—A Minireview of Basic Concepts and Recent Advancements,” Journal of Hand Therapy 25, no. 2 (2012): 138; M. K. Drew and C. Purdam, “Time to bin the term ‘overuse’ injury: is ‘training load error’ a more accurate term?,” British journal of sports medicine 50, no. 22 (2016).

[18] A. Del Buono et al., “Tendinopathy and inflammation: some truths,” International journal of immunopathology and pharmacology 24, 1 Suppl 2 (2011): 45; Jessica E. Ackerman et al., “Obesity/Type II diabetes alters macrophage polarization resulting in a fibrotic tendon healing response,” PLOS ONE 12, no. 7 (2017); Tom A. Ranger et al., “Is there an association between tendinopathy and diabetes mellitus? A systematic review with meta-analysis,” British journal of sports medicine 50, no. 16 (2016).

[19] J. E. Taunton et al., “A retrospective case-control analysis of 2002 running injuries,” British journal of sports medicine 36, no. 2 (2002): 98.

[20] Esra Circi et al., “Biomechanical and histological comparison of the influence of oestrogen deficient state on tendon healing potential in rats,” International Orthopaedics 33, no. 5 (2009): 1466; Stephen H. Liu et al., “Estrogen Affects the Cellular Metabolism of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament,” The American journal of sports medicine 25, no. 5 (2016): 704; W. D. Yu et al., “Combined effects of estrogen and progesterone on the anterior cruciate ligament,” Clinical orthopaedics and related research, no. 383 (2001): 281.

[21] James E. Gaida et al., “Asymptomatic Achilles tendon pathology is associated with a central fat distribution in men and a peripheral fat distribution in women: a cross sectional study of 298 individuals,” BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 11, no. 1 (2010).

[22] Peter Malliaras et al., “Patellar Tendinopathy: Clinical Diagnosis, Load Management, and Advice for Challenging Case Presentations,” The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy 45, no. 11 (2015): 895.

[23] Nicola Maffulli, “The Royal London Hospital Test for the clinical diagnosis of patellar tendinopathy,” Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal 7, no. 2 (2017).

[24] S. de Jonge et al., “Relationship between neovascularization and clinical severity in Achilles tendinopathy in 556 paired measurements,” Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports 24, no. 5 (2014).

[25] Seán McAuliffe et al., “Can ultrasound imaging predict the development of Achilles and patellar tendinopathy? A systematic review and meta-analysis,” British journal of sports medicine 50, no. 24 (2016).

[26] Brett M. Andres and George A. C. Murrell, “Treatment of tendinopathy: what works, what does not, and what is on the horizon,” Clinical orthopaedics and related research 466, no. 7 (2008): 1542.

[27] J. L. Cook and C. R. Purdam, “Is tendon pathology a continuum? A pathology model to explain the clinical presentation of load-induced tendinopathy,” British journal of sports medicine 43, no. 6 (2009): 413.

[28] P. Jonsson, “Superior results with eccentric compared to concentric quadriceps training in patients with jumper's knee: a prospective randomised study,” British journal of sports medicine 39, no. 11 (2005); C. R. Purdam, “A pilot study of the eccentric decline squat in the management of painful chronic patellar tendinopathy,” British journal of sports medicine 38, no. 4 (2004); Craig R. Purdam et al., “Discriminative ability of functional loading tests for adolescent jumper's knee,” Physical Therapy in Sport 4, no. 1 (2003); M. A. Young, “Eccentric decline squat protocol offers superior results at 12 months compared with traditional eccentric protocol for patellar tendinopathy in volleyball players,” British journal of sports medicine 39, no. 2 (2005).

[29] Peter Malliaras, Lower Limb Tendinopathy Course (London, 31.10.2016), p. 12; Peter Malliaras et al., “Achilles and patellar tendinopathy loading programmes: A systematic review comparing clinical outcomes and identifying potential mechanisms for effectiveness,” Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) 43, no. 4 (2013).

[30] L. J. Cannell, “A randomised clinical trial of the efficacy of drop squats or leg extension/leg curl exercises to treat clinically diagnosed jumper's knee in athletes: pilot study,” British journal of sports medicine 35, no. 1 (2001).

[31] Ebonie Rio et al., “Isometric exercise induces analgesia and reduces inhibition in patellar tendinopathy,” British journal of sports medicine 49, no. 19 (2015): 1281.

[32] Maria E. H. Larsson, Ingela Käll, and Katarina Nilsson-Helander, “Treatment of patellar tendinopathy—a systematic review of randomized controlled trials,” Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 20, no. 8 (2012): 1643.

[33] Stasinopoulos Dimitrios, Manias Pantelis, and Stasinopoulou Kalliopi, “Comparing the effects of eccentric training with eccentric training and static stretching exercises in the treatment of patellar tendinopathy. A controlled clinical trial,” Clinical rehabilitation 26, no. 5 (2012).

[34] Peter Malliaras, Lower Limb Tendinopathy Course (London, 31.10.2016), pp. O5.

[35] P. Manias and D. Stasinopoulos, “A controlled clinical pilot trial to study the effectiveness of ice as a supplement to the exercise programme for the management of lateral elbow tendinopathy,” British journal of sports medicine 40, no. 1 (2006).

[36] Ibid.

[37] A. de Vries et al., “Effect of patellar strap and sports tape on pain in patellar tendinopathy: A randomized controlled trial,” Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports 26, no. 10 (2016).

[38] de Vries, Astrid J et al., “Effect of a patellar strap on the joint position sense of the symptomatic knee in athletes with patellar tendinopathy,” Journal of science and medicine in sport (2017).

[39] Adam B. Rosen, Jupil Ko, and Cathleen N. Brown, “Single-limb landing biomechanics are altered and patellar tendinopathy related pain is reduced with acute infrapatellar strap application,” The Knee 24, no. 4 (2017).

[40] Adam B. Rosen et al., “Patellar tendon straps decrease pre-landing quadriceps activation in males with patellar tendinopathy,” Physical therapy in sport : official journal of the Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Sports Medicine 24 (2017).

[41] Gali Dar and Einat Mei-Dan, “Immediate effect of infrapatellar strap on pain and jump height in patellar tendinopathy among young athletes,” Prosthetics and Orthotics International 43, no. 1 (2018).

[42] Brett M. Andres and George A. C. Murrell, “Treatment of tendinopathy: what works, what does not, and what is on the horizon,” Clinical orthopaedics and related research 466, no. 7 (2008): 1542.

[43] Rachel Chester et al., “Eccentric calf muscle training compared with therapeutic ultrasound for chronic Achilles tendon pain--a pilot study,” Manual therapy 13, no. 6 (2008); S. J. Warden et al., “Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound for chronic patellar tendinopathy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial,” Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 47, no. 4 (2008); Maria E. H. Larsson, Ingela Käll, and Katarina Nilsson-Helander, “Treatment of patellar tendinopathy—a systematic review of randomized controlled trials,” Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 20, no. 8 (2012): 1645.

[44] Mark F. Reinking, “CURRENT CONCEPTS IN THE TREATMENT OF PATELLAR TENDINOPATHY,” International journal of sports physical therapy 11, no. 6 (2016).

[45] Brett M. Andres and George A. C. Murrell, “Treatment of tendinopathy: what works, what does not, and what is on the horizon,” Clinical orthopaedics and related research 466, no. 7 (2008): 1542.

[46] Angelo de Carli et al., “Calcific tendinitis of the shoulder,” Joints 2, no. 3 (2014): 133.

[47] U. Fredberg et al., “Ultrasonography as a tool for diagnosis, guidance of local steroid injection and, together with pressure algometry, monitoring of the treatment of athletes with chronic jumper's knee and Achilles tendinitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study,” Scandinavian journal of rheumatology 33, no. 2 (2004).

[48] L. Bisset et al., “Mobilisation with movement and exercise, corticosteroid injection, or wait and see for tennis elbow: randomised trial,” BMJ 333, no. 7575 (2006).

[49] M. Kongsgaard et al., “Corticosteroid injections, eccentric decline squat training and heavy slow resistance training in patellar tendinopathy,” Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports 19, no. 6 (2009); Brooke K. Coombes et al., “Effect of corticosteroid injection, physiotherapy, or both on clinical outcomes in patients with unilateral lateral epicondylalgia: a randomized controlled trial,” JAMA 309, no. 5 (2013).

[50] Jianying Zhang, Camille Keenan, and James H.-C. Wang, “The effects of dexamethasone on human patellar tendon stem cells: implications for dexamethasone treatment of tendon injury,” Journal of orthopaedic research : official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society 31, no. 1 (2013); Ronald Hugate et al., “The effects of intratendinous and retrocalcaneal intrabursal injections of corticosteroid on the biomechanical properties of rabbit Achilles tendons,” The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume 86-A, no. 4 (2004).

[51] Micheal P. Hall, James P. Ward, and Dennis A. Cardone, “Platelet Rich Placebo?: Evidence for Platelet Rich Plasma in the Treatment of Tendinopathy and Augmentation of Tendon Repair,” Bulletin of the Hospital for Joint Diseases 71 (2013): 57; Nasir Hussain, Herman Johal, and Mohit Bhandari, “An evidence-based evaluation on the use of platelet rich plasma in orthopedics – a review of the literature,” SICOT-J 3, no. 1 (2017); Peter Malliaras et al., “Patellar Tendinopathy: Clinical Diagnosis, Load Management, and Advice for Challenging Case Presentations,” The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy 45, no. 11 (2015): 894; de Vos, Robert J et al., “Platelet-rich plasma injection for chronic Achilles tendinopathy: a randomized controlled trial,” JAMA 303, no. 2 (2010); Robert-Jan de Vos, Johann Windt, and Adam Weir, “Strong evidence against platelet-rich plasma injections for chronic lateral epicondylar tendinopathy: a systematic review,” British journal of sports medicine 48, no. 12 (2014); Franciele Dietrich et al., “Effect of platelet-rich plasma on rat Achilles tendon healing is related to microbiota,” Acta Orthopaedica 88, no. 4 (2017).

[52] Lane M. Sanderson and Alan Bryant, “Effectiveness and safety of prolotherapy injections for management of lower limb tendinopathy and fasciopathy: a systematic review,” Journal of foot and ankle research 8, no. 1 (2015); O. Morath et al., “The effect of sclerotherapy and prolotherapy on chronic painful Achilles tendinopathy-a systematic review including meta-analysis,” Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports 28, no. 1 (2018); Ulrike H. Mitchell et al., “The Construction of Sham Dry Needles and Their Validity,” Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2018, no. 5 (2018); Patrick C. Wheeler et al., “A Comparison of Two Different High-Volume Image-Guided Injection Procedures for Patients With Chronic Noninsertional Achilles Tendinopathy: A Pragmatic Retrospective Cohort Study,” The Journal of Foot and Ankle Surgery 55, no. 5 (2016); F. A. Chaudhry, “Effectiveness of dry needling and high-volume image-guided injection in the management of chronic mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy in adult population: a literature review,” European Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery & Traumatology 27, no. 4 (2017): 446.

[53] Antonio Pascarella et al., “Arthroscopic management of chronic patellar tendinopathy,” The American journal of sports medicine 39, no. 9 (2011).

[54] F. A. Chaudhry, “Effectiveness of dry needling and high-volume image-guided injection in the management of chronic mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy in adult population: a literature review,” European Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery & Traumatology 27, no. 4 (2017): 447.

[55] N. Maffulli et al., “Surgical management of tendinopathy of the main body of the patellar tendon in athletes,” Clinical journal of sport medicine : official journal of the Canadian Academy of Sport Medicine 9, no. 2 (1999); Peter Malliaras, Lower Limb Tendinopathy Course (London, 31.10.2016).

[56] N. Maffulli et al., “Surgical management of tendinopathy of the main body of the patellar tendon in athletes,” Clinical journal of sport medicine : official journal of the Canadian Academy of Sport Medicine 9, no. 2 (1999).

[57] Joshua S. Everhart et al., “Treatment Options for Patellar Tendinopathy: A Systematic Review,” Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association 33, no. 4 (2017).

[58] Carla van Usen and Barbara Pumberger, “Effectiveness of Eccentric Exercises in the Management of Chronic Achilles Tendinosis,” The Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and Practice 5, no. 2 (2007): 8, http://ijahsp.nova.edu/articles/vol5num2/van_Usen.pdf.